September is Suicide Prevention Awareness Month, and you may have seen the videos on the news, YouTube, Facebook, LinkedIn, Instagram or other media platforms that are meant to raise awareness of suicide, especially that of suicide by veterans with the 22 Push-up Challenge. But suicide affects everyone and sparks many different emotions among the living. Whether that person was a veteran who saw combat, someone who made you laugh, someone with gifts and creativity that you admired, or someone who’d smile and nod at you while on a walk in a quiet neighborhood, the death of that person by their own hand is bound to leave you sorrowful, sympathetic toward the family and, overall, incredibly confused.

In March of 2019, Dr. Melinda Moore Ph.D., presented a lecture at Divine Mercy University entitled “How to Understand Suicide and its Aftermath: From a Scientific & Faith Perspective.”

She is a licensed clinical psychologist and an assistant professor of psychology at Eastern Kentucky University. She also sits on the board of the American Association of Suicidology.

She shared her first-hand experience of suicide — when her husband killed himself — and how it affects the living. At the time, her husband was a chemist and grad student at Ohio State University.

“This was, without a doubt,” she said, “the most emotionally and physically painful experience of my life, and it changed me in a very profound way. What I experienced was an incredible professional and personal rejection. I realized that, when I returned to work, that something different was going on. There was something about this experience I shared in the taint of what he had done.”

During her presentation, Dr. Moore referenced the article “Struggling to Understand Suicide” by Fr. Ron Rolheiser, a priest in the Missionary Oblates of Mary Immaculate (OMI) and the president of the Oblate School of Theology in San Antonio, Texas.

“All death unsettles us,” writes Fr. Rolheiser. “But suicide leaves us with a very particular series of emotional, moral, and religious scars. It brings with it an ache, a chaos, a darkness, and a stigma that has to be experienced to be believed. Sometimes we deny it, but it’s always there, irrespective of our religious and moral beliefs.”

We all know the great actor and comedian Robin Williams, who brought so much laughter and joy to us from the stage and the silver screen, left the world shocked when he commited suicide. Chester Bennington — the voice of Linkin Park, one of the most successful rock bands of the new millenium — took his own life at his California home while his family was away on vacation nearly a year after his good friend Chris Cornell (Soundgarden and Audioslave vocalist) committed suicide, and fashion designer Kate Spade fashioned a suicide note before committing suicide at her apartment in Manhattan, New York.

Even in a small town like Warrenton, Virginia, an elderly couple was discovered deceased in their home when their home healthcare provider discovered a note on their front door saying not to enter because of their suicide in the residence.

In each of the cases just mentioned — like many others — there were symptoms and warning signs that went unnoticed or neglected. Williams and Bennington had both battled addiction and depression throughout their lives. Williams was even being treated for depression and anxiety before his death, and had been diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease months before. Bennington’s widow admits today that she’s more educated about the warning signs leading to her husband’s suicide: hopelessness, changes in behavior, and isolation. Neighbors and friends of the couple in Virginia, including Sadia LaRose who had lived across the street from them, compared them to Romeo and Juliet despite their health and financial burdens. But LaRose admitted that she would have intervened in some way had she been aware of their plan.

“If any of us knew, we would have gone over there to try to stop it,” said LaRose, as reported by the Fauquier Times.

And it’s not just adults, veterans and celebrities. Children also struggle with suicidal thoughts and impulses. In 2018, a new study released by the American Academy of Pediatrics showed that more kids are either contemplating or attempting suicide. That study was followed by the August death of 9-year-old Jamel Myles of Colorado, who committed suicide after telling his fourth grade classmates that he was gay. In May of 2016, Billy Sechrist discovered his 15-year-old daughter, Shania, after she committed suicide in their Pennsylvania home. A freshman in high school, Shania had left a note explaining that, while she loved her family, she couldn’t bear the pain of being bullied any more. The following winter, an 8-year-old boy, a third grader in Cincinnati named Gabriel Taye, was beaten by bullies at school and, two days later, young Gabriel ended his life in his own bedroom.

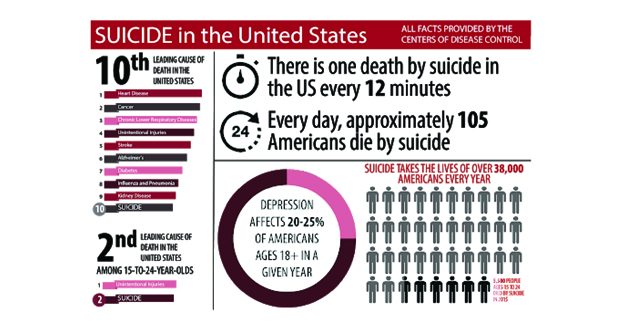

Suicide is the 10th leading cause of death in the United States. It is also the second leading cause of death in the world for those aged 15-24 years and is often considered a public health emergency. In the aftermath of suicide, we are often left with the hopelessness of hindsight, telling ourselves, “if we had only known, we would have done something to stop it.”

According to a recent report released by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the suicide rate in the United States has jumped 33 percent since 1999, with over 47,000 Americans ending their own lives in 2017. The report also showed that public funding to research, prevent, and combat suicide is far below that of research of other leading causes of death and conditions with lower mortality rates. The National Institute of Health spent about $68 million on suicide last year. The NIH spent nearly twice as much researching indoor pollution, over three times as much on dietary supplements, five times as much studying sleep, and ten times more on breast cancer.

“What I’m just painfully aware of is that all of the areas where the top 10 causes of death in the United States have gone down have received significantly more attention,” said John Draper, director of the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline, in an interview with USA Today. “There’s been so much more put into every one of those causes of death than suicide … If you didn’t do anything for heart disease and you didn’t do anything for cancer, then you’d see those rates rise, too.”

Dr. Moore experienced a similar disconnect from suicide by the people around her. At the time of her husband’s death, she was a policy analyst and a speechwriter for the director of public health in Ohio. People were normally happy to see her, but she noticed a real change when she returned to work after burying her husband in his home nation of Ireland.

“When I would see people after I came back,” she said, “they were clearly not interested in me coming to their office, and they were certainly not coming to mine. When I would see people in the hallway, they would turn and walk away in the opposite direction. There was an enormous professional isolation and rejection. Also my family and friends had no interest in talking about this, so there was enormous personal rejection and isolation.”

But just as it was the worst experience of her life, Dr. Moore also looked at her experience with suicide as the best experience of her life.

“That may seem absurd,” she explained, “but it really took the blinders off and changed me on a profound level. It made me more compassionate, it certainly changed my vocational interests. I was the first researcher to look at post-traumatic growth among suicide bereaved parents and, when considering my dissertation at CUA [Catholic University of America], I understood that nobody knows more about the inside out than me. Now my primary research is in primarily post-traumatic growth, and I embed it in everything I do.”

Watch the entire recording of the suicide lecture to learn how a faith-based approach to mental disorders can help save lives.

If you or someone you know may need help, here are two suicide prevention resources:

- National Suicide Prevention Lifeline: 1-800-273-8255

- Crisis Text Line: Text HOME to 741741

You can also equip yourself with the skills to recognize and help those on the dark, slippery slope toward suicide.

In DMU’s psychology and counseling programs, we teach students how to act effectively in situations where de-escalation, negotiation, and crisis intervention are needed, such as suicide attempts. The courses also train students on the best ways to diagnose and treat common psychological problems to prevent severe disorders from developing. Sign up to learn more.