There are two things that many of us seem to get wrong: the days leading up to Christmas, and the days leading up to Easter.

In the days leading up to Christmas–which can begin as early as May–we find ourselves in a consistent rush: fixing budgets, planning trips, scheduling reunions, flying to pageants and concerts, collecting items for feasts and bakefests, and purchasing lots and lots and lots of presents. We leave very little time and room for reflection, charity, prayer, and preparation for Christ’s arrival.

With Christmas now past and the liturgical season of ordinary time coming to a close, our attention turns toward Easter, and the season of Lent from Ash Wednesday to Good Friday, where we follow Jesus on his adult journey of teaching, ministry, prayer, healing and suffering right up to his crucifixion and death on Good Friday. Tradition held by Catholics and Christians around the world maintains the element of sacrifice, of “giving up” something for the whole 40-day season of Lent.

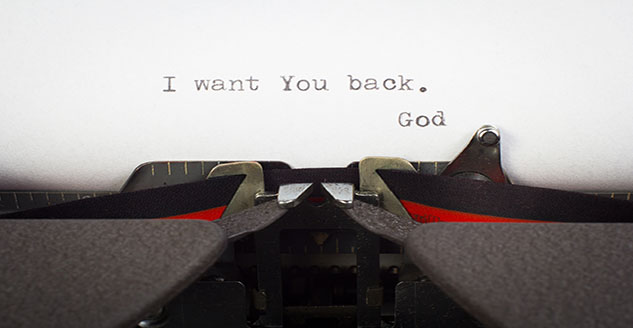

So how do we get the original meaning of Lent wrong? We engage in the tradition for all the wrong reasons. Like Christmas, we take Christ out of Lent.

We may not do so consciously, but we often find ourselves using Lent to achieve internal or worldly goals. We give up junk food or monitor what we eat when starting a new diet, or abstain from beer to lower the cholesterol and clear the mind. We give up some TV so we can manage time better or focus on other interests.

“We all have these interior movements,” said Divine Mercy University Adjunct Professor Dr. Ian Murphy during last month’s webinar titled The Power of Habit: Therapeutic Techniques From St. Thomas Aquinas. “What St. Thomas Aquinas teaches us is that these interior movements–these appetites, these passions, these emotions–are not the bad guy, but we can’t do whatever they say. If we do whatever they tell us to do, then we’re not truly free of them. We become slaves to them. But we can’t ignore them either. They’re an integral part of us, and they were originally created to support our happiness.”

We may see the season of Lent as a second chance with the New Year’s resolution we missed, except with a partially structured strategy and timeline. Even in the Church, many of us confuse worldly growth or preparation with spiritual growth or preparation. But in doing so, we might become more worried about staying on track with a certain practice, instead of considering if that particular practice is helping to actually convert our hearts, allow us to analyze the depth of Christ’s sacrifice and teachings on earth, and bring us closer to God in the first place, because Lent is about re-centering our will to His and living that out in the world.

“We can think of Lent as a time to eradicate evil or cultivate virtue,” said Blessed Fr. Fulton Sheen, “a time to pull up weeds or to plant good seeds. Which is better is clear, for the Christian ideal is always positive rather than negative. A person is great not by the ferocity of his hatred of evil, but by the intensity of his love for God. Asceticism and mortification are not the ends of a Christian life; they are only the means. The end is charity. Penance merely makes an opening in our ego in which the Light of God can pour. As we deflate ourselves, God fills us. And it is God’s arrival that is the important event.”

A good Lenten practice would actually be for us to take spiritual inventory of our lives and determine where we need growth. One means of doing this, especially during the season of Lent, is what’s called Virtuous Habit Formation. St. Thomas Aquinas defines virtue as an operative disposition toward the good. In other words, virtues are repeated performative actions that internalize into perfective habits that form our character according to our ultimate purpose.

“We don’t do whatever our feelings, passions, and appetites tell us to do,” said Dr. Murphy. “In other words, we don’t do whatever our ‘inner selves’ say. But we don’t ignore our feelings either. Rather, we appreciate our emotions as an integral part of us. We consult our emotions for illumination as we discern; and with a conscious receptivity to the Holy Spirit, we allow prudence to order our emotions. And we also allow emotion to wake up the powers of the soul whenever rationality and will grow cold and lose sight of their higher calling.”

Those interior movements mentioned earlier can become disordered within us, and in their disorder, they can wreak havoc. Consider that person who does offer that up moderate drinking upon returning home. After a hard day’s work or a day full of stress and anxiety, that person may be looking forward to that nearly instant gratification of relaxation and stress reduction. Despite any health or anxiety benefits, the frequent repetition of this practice wires the mind to expect; that person becomes disposed to pursuing those glasses of wine or pints of lager after each hard day, and may begin to see it as a regular remedy to a lingering stress.

“All this is the key to our therapeutic technique: repeat actions,” said Dr. Murphy. “If the acts be multiplied–if you keep doing things over and over again, even a small thing, an allegedly tiny baby step–if you repeat it, a switch is thrown inside of you, and the synaptic pathways in our brains are rewired. We become inclined to behave that way. We become disposed to behave that way.”

Our “giving something up” for Lent is not merely an offering in the Lenten tradition of sacrifice, or an offering in reverence to Christ’s sacrifice, or just us utilizing the season as an annual detox, fat burner or dietary starting point. When we remove the worldly value of the things we offer up–when we apply virtue to our commitment to change our habits–we understand that we’re not just giving something up. We’re giving something over, and the less we take, the more we open ourselves to the richnesses of God’s love, filling the voids left by our bottles of our worldly desires.

“This is the key to our wellbeing,” said Dr. Murphy, “to our flourishing, to our happiness. We are created, we are fallen, and we’re also redeemed. In our fallenness, things that were created for good get disordered. But in our redemption, they can be re-ordered again.”

Lent is not our mulligan when we miss our New Year’s resolution. It is not our self-improvement project, our annual detox or our new diet plan. Lent is a renewal of our promise to walk with Jesus into the desert, into the city streets, even to the foot of the cross, with our hands in His the whole way. Lent is about our relationship with God and with Christ; and that relationship, like any other, has trials, distress and joy.

Sign up to learn more about Divine Mercy University’s graduate programs in counseling and/or psychology.